Industry Focus: Sensor advances allow pipeline leak detection to take to the skies

Sustainability and green initiatives have always been laudable objectives, with mission statements around the world confirming commitments to lower emissions and energy consumption, and increase recyclability, to name a few.

However, increasingly over recent years, sustainability has also morphed into a business imperative, as investors, stakeholders and shareholders begin to steer their preferences towards companies that are not just paying lip service to the green agenda but are, instead, actively looking for ways to make their overall carbon footprint and environmental impact as low as possible.

First, the focus was on coal; now, the oil industry thinks it might be next. Indeed, a recent article in Forbes magazine stated: “One of the primary reasons that all three big companies (e.g., BT, Chevron, ExxonMobil) are so focused on reducing their emissions of methane and other greenhouse gases is simple: they view it as being in their best economic interest, rather than risk seeing investors flee to other industry segments perceived as being more environmentally friendly.”

These big three companies—coupled to numerous other large, medium and small companies—can have a hugely positive impact on the reduction of unwanted methane emissions. This is especially true when you consider that, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), the natural gas pipeline network in the continental U.S. comprises about 3 MM mi of interstate and intrastate pipelines that link natural gas production areas and storage facilities with consumers. In 2019, this natural gas transportation network delivered approximately 28 Tft3 of natural gas to 77 MM customers.

If investor pressure is not enough, stricter legislation is also forcing companies to appraise the way they install and—arguably, more importantly—maintain their networks. The U.S. Department of Transportation’s Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) published an advisory bulletin in June this year that, in summary, states: “PHMSA is issuing this advisory bulletin to remind each owner and operator of a pipeline facility that the ‘Protecting our infrastructure of pipelines and enhancing safety act of 2020’ (PIPES Act of 2020) contains a self-executing mandate requiring operators to update their inspection and maintenance plans to address eliminating hazardous leaks and minimizing releases of natural gas (including intentional venting during normal operations) from their pipeline facilities. Operators must also revise their plans to address the replacement or remediation of pipeline facilities that are known to leak based on their material, design, or past operating and maintenance history. The statute requires pipeline operators to complete these updates by December 27, 2021.”

Obviously, a potentially significant time gap exists between updating plans and actually executing them, but this gives companies the breathing room to source and integrate technologies and procedures that will provide the best possible means to monitor and maintain their pipeline infrastructures. In fact, the PIPES Act of 2020 directs gas pipeline operators to use advanced leak-detection technologies to conduct leak detection and repair programs that protect the environment and enhance pipeline safety.

Reactive and proactive maintenance are key facets contributing to the efficient operation of any system—big or small, consumer or commercial. In most cases, the expenditure of time and effort is justified in financial terms, but fiscal matters are only part of the full picture. In the case of pipelines, leaks and their resulting environmental impact must now also be factored in and given equal, if not higher, billing.

The primary driver and antagonist in all of this is methane, the main component of natural gas. Methane emissions have increased by 9% globally in the last decade. Although naturally occurring, huge amounts of methane are emitted from man-made sources, such as coal mining, landfill, wastewater treatment and, of course, oil and natural gas production and transportation.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) explains why: “Methane is the second most abundant anthropogenic (human-caused) greenhouse gas after carbon dioxide (CO2), accounting for about 20% of global emissions. It is more than 25 times as potent as CO2 at trapping heat (over 100 yr) in the atmosphere and over the last two centuries, methane concentrations in the atmosphere have more than doubled, largely due to human-related activities. Because methane is both a powerful greenhouse gas and short-lived compared to CO2, achieving significant reductions would have a rapid and significant effect on atmospheric warming potential.”

Looking at it positively, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change elaborates: “A Global Methane Assessment released in May by the Climate and Clean Air Coalition (CCAC) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), shows that human-caused methane emissions can be reduced by up to 45% this decade. Such reductions would avoid nearly 0.3°C of global warming by 2045 and would be consistent with keeping the goal of the Paris Agreement to limit global temperature rise to 1.5°C (2.7°F) within reach.”

The International Energy Agency’s (IEA’s) Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS) says that emissions from the pipeline sector will need to fall to around 20 metric tpy by 2030—a drop of more than 70% from levels in 2020.

Finally, and somewhat under the radar, U.S. President Biden also issued an executive order in May 2021 directing federal agencies to incorporate the economic risks from climate change into decision-making. Although this does not specifically address fossil fuel investments, the concern among energy producers is that financial regulators will ultimately use their power to steer banks and investors away from the industry.

This raft of national and international legislation is setting a very high bar for the natural gas industry, not just in the U.S., but around the world. The problem is that the scale of operations that must be addressed is immense. The 3 MM mi of pipelines in the U.S. alone—some of it in incredibly remote areas—present a massive undertaking for reactive maintenance, let alone proactive.

Mobile gas leak detection technologies—both portable and vehicle-mounted—do exist, and are ideal for easier-to-access locations. However, when the hostile and sometimes near impenetrable or inaccessible nature of some locations is considered, even the most rugged 4×4 vehicle will have issues.

Aware of this impending legislation and the ethical, financial, societal and political turmoil behind it, development work has been put in motion to enhance sensor technology and, more importantly, make it far more portable.

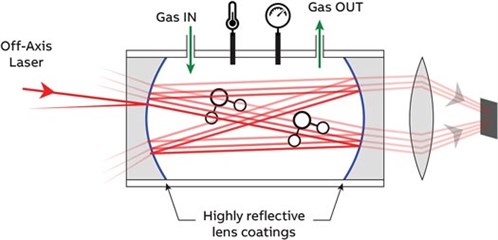

Drone technology is the answer. Thanks to significant advances in sensor technology, especially those relating to cavity enhanced laser absorption spectroscopy techniques, methane can now be detected with a sensitivity more than 1,000 times higher and over 10 times faster than conventional leak-detection tools. More importantly, this technology is not only sensitive and fast, but also small enough to be mounted on commercial drones.

The author’s company has released a new technologya that can be mounted on low-cost commercial UAVs capable of carrying 3 kg (6.6 lb) payloads (FIG. 1). Flying at altitudes of 40 m (130 ft), or higher, and at speeds up to 88 km/hr (55 mph), the drone-mounted solutiona can detect, quantify and map leaks up to 100 m (328 ft) from natural gas distribution and transmission pipelines, gathering lines, storage facilities and other potential methane emissions sources.

|

|

FIG. 1. The drone-mounted solutiona can detect, quantify and map leaks up to 100 m (328 ft) from natural gas distribution and transmission pipelines, gathering lines, storage facilities and other potential methane emissions sources. |

Previous leak-detection efforts relied on slow, qualitative, analog sensors or expensive delicate cameras to find leaks, but the extremely fast response and high precision of the new analyzer technology (FIG. 2) allows scientists and researchers to reliably quantify greenhouse gas fluxes, which provides important information when studying the complex environmental processes affecting climate and pollution.

|

| FIG. 2. The gas leak detectora enables scientists and researchers to reliably quantify greenhouse gas fluxes, providing important information when studying the complex environmental processes affecting climate and pollution. |

This new drone-based systema has become available at the ideal time for pipeline operators. Based on the stipulations in the PIPES Act of 2020, operators can now update maintenance plans with the knowledge that the technology is available to make remote leak detection a far simpler and cost-effective proposition. These advances in sensor technology are not restricted to drones—they can also be easily deployed in vehicles and handheld monitoring systems, providing a defense-in-depth approach to detect, map and quantify large, small and even hidden leaks with unprecedented speed, reliability and accuracy throughout the entire natural gas infrastructure, including upstream, midstream, downstream and gas utilities. GP

NOTES

a ABB’s HoverGuard

|

DOUG BAER is the Global Product Line Manager for laser analyzers within the ABB Measurement and Analytics Division, where he invents, develops, manufactures and sells laser-based instrumentation for ultra-sensitive and accurate measurements of gases, liquids and isotope ratios for atmospheric and environmental monitoring, industrial process control and homeland security. Dr. Baer is an inventor of ABB’s patented laser-based technology and the industry-leading natural gas leak detection platform. Before joining ABB, he served as the President of Los Gatos Research. Dr. Baer earned a BS degree in engineering physics from the University of California, Berkeley, and an MS degree and PhD in mechanical engineering from Stanford University.

Comments