Distance and politics mean no easy solution to Russia’s pipeline problem

Russia has largely been able to maintain its oil exports despite de jure and de facto restrictions on destination, mode of transit and price. But it does not have the same luxury of flexibility when it comes to gas. Time, distance, cost and politics are all against it finding a solution to its gas export problem.

Russia sent 167bn m³ of gas to Europe in 2021 but only c.60bn m³ in 2022, a volume that could fall further still. If Russia wants to find new markets for this gas to the east, it will need to access or build infrastructure to move stranded production out of Western Siberia.

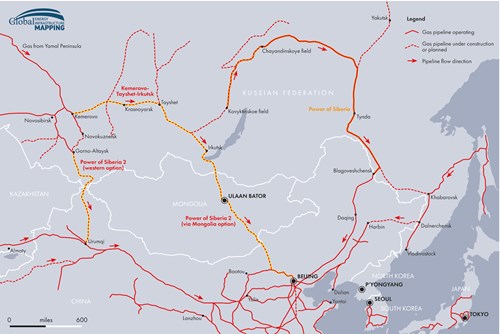

Power of Siberia 2, Russia’s long-in-development pipeline designed to send additional gas to China, has taken on a new importance in the past year because of Moscow’s collapsing energy relationship with Europe. The proposed route for the Soyuz–Vostok portion of the pipeline would run from Irkutsk, across Mongolia and onwards to Beijing. It would carry 50–80bn m³/yr of gas.

The Russian route of Power of Siberia 2 is not yet confirmed, but to bring enough gas as far as Irkutsk and utilise Soyuz–Vostok’s nameplate capacity it will need to run to the West Siberian basin. The details of the Russian section of the pipeline have not been revealed yet. Reportedly, Gazprom will connect it to the Bovanenkovo gas field, bringing the pipeline’s total length to 2,450 miles. Due to limited capacity on the soon to be operational Kemerovo – Tayshet – Irkutsk pipeline and on pipelines further west, the Russian section of the pipeline will require significant construction from Bovanenkovo to Irkutsk.

|

|

The likely Mongolian route of Power of Siberia 2 and the earlier, now cancelled, western option which would have run over the Altai Mountains.

|

From Bovanenkovo to Beijing is 650 miles further than Bovanenkovo to Berlin, and through more difficult terrain with minimal existing infrastructure. In addition, the Mongolian portion of the pipeline runs through a seismically active area. Combined with the impact of sanctions—which limit Russian access to Western technology and capital—the massive project may be prohibitively expensive and its already distant 2030 announced startup date could slip further into the future.

Existing pipelines through Central Asia could also serve to send Russian gas east. The Central Asia–Centre (CAC) pipeline is a little-used, Soviet-era connection that previously sent gas from Central Asia north, through Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, interconnecting with the Russian domestic gas transmission near Saratov.

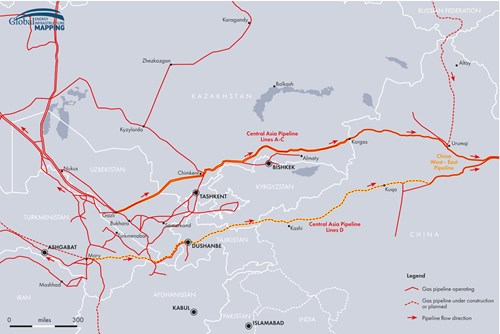

The 55bn m³/yr Central Asia–China pipeline system runs from Turkmenistan to China, and when the planned Line D is completed, its capacity will expand by an additional 30bn m³/yr. Existing capacity is underused: only 40bn m³ of gas reached China via the pipeline in 2021. In combination, the two sets of pipelines could give 50–80bn m³/yr of Russian gas access to the Chinese market.

|

| Central Asia-China Pipelines A-C and the planned Central Asia-China Pipeline D, which also passes through Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan on its way to China. |

But this alternative comes with a set of political challenges. The Central Asian transit countries are, like Ukraine, post-Soviet states with long histories of being ruled from Moscow. Russian revanchism in Europe has raised alarms. In addition, gas production in Turkmenistan has steadily risen since 2017, to 79.3bn m³ in 2021. Russian gas would compete with these exports, making a big gas transit deal less likely.

Existing Russian gas exports to China draw on fields in Eastern Siberia and off the coast of the Pacific island of Sakhalin. Since 2020, they have travelled mainly via the recently constructed Power of Siberia 1 pipeline, although two others are in development. However, none of these can transport gas from the main centre of Russian gas production in Western Siberia.

The West Siberian basin stretches across the northwestern Russian provinces of Yamal-Nenets and Khanty-Mansi, and contains more than 100 giant gas fields and ten supergiant fields. This basin has seen heavy investment in gas extraction, with 81pc of Russia’s 637.3bn m³ of gas production originating in Yamal-Nenets alone in 2020.

Russia’s bifurcated gas transmission system means existing pipelines allow very little of the gas produced in Western Siberia to flow to Russia’s eastern neighbours. Pipelines run from Western Siberia south and east, but by the time they reach Kemerovo—to the north of the Altai mountains— the pipelines have shrunk to 21” in diameter and nameplate capacity is only 22.5bn m³/yr, all of which serves the domestic market. The planned Kemerovo–Tayshet–Irkutsk pipeline, which is expected to begin operations in 2023, would carry Russian gas further east, but capacity would be limited to 8bn m³/yr.

Three-quarters of Russian production was consumed domestically in 2021. But almost all the rest went west to Europe from the West Siberian basin. The west-facing pipeline network necessary to sustain these exports has been in development since the 1970s, and investment has continued throughout the last decade.

Since 2011, 6,237 miles of 48” or more diameter pipeline associated with the system has been completed. The largest pipeline projects built in the last decade as part of this export infrastructure are the two Bovanenkovo—Ukhta pipelines, both 745 miles long with 57.5bn m³/yr nameplate capacities, and the Nord Stream 1 and 2 pipelines, 761 and 759 miles long respectively with 55bn m³/yr nameplate capacities. Altogether, they cost close to $65bn. By the end of 2021, nameplate pipeline capacity for Russian exports to Europe was close to 250bn m³/yr.

Power of Siberia 2’s 50–80bn m³/yr capacity stacks up poorly against this existing infrastructure. And based on the cost of other pipelines recently completed in Russia, the expense of Power of Siberia 2 may be prohibitive. The pipeline portion of the Power of Siberia 1, which ran 1,462 miles to the Chinese border, had an estimated price tag of c.$10bn by 2020, when it first began delivering gas. The Bovanenkovo–Ukhta pipelines, including other infrastructure built to support their construction and operation, cost $20bn each.

Furthermore, as an international project, Power of Siberia 2 will be vulnerable to political difficulties. An earlier version of Power of Siberia 2 would have taken a more western route, running directly to China via the Altai mountains. The route was shelved in 2019 due to Chinese opposition relating to its proximity to sacred Buddhist sites and important ecological areas.

The Power of Siberia 2 project is nonetheless underway. In July 2022, the Mongolian prime minister said he expected construction to begin in 2024, and some engineering work has begun. No long-term gas deal directly related to the project has been signed between China and Russia, but talks are in progress. In March, the Russian deputy prime minister said a deal was close. Yet the project’s limited capacity, high cost and long development time make potential gas sales via the pipeline a poor substitute for European export markets.

Adding potential exports via the Central Asia route to Power of Siberia 2 could allow Russia to match its 2021 European exports. And the Central Asian route has the potential to begin operating much more quickly. In a promising turn of events for Moscow, Gazprom signed gas cooperation roadmaps in January with Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

Few details are available, but the roadmaps reportedly cover Russian gas exports to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan’s domestic markets, which together consumed c.50bn m³ of gas in 2021. But both Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan were careful in their public statements to say that no local infrastructure was to be surrendered to Gazprom’s control as part of the deal. When discussing an earlier Russian attempt at a gas deal in 2022, Kazakh energy minister Bulat Aqchulaqov made it clear that Kazakhstan would accept no political conditions as part of the agreement.

On 15 February, Gazprom CEO Alexei Miller visited Ashgabat, where he met with Turkmenistan’s president, Serdar Berdymukhammedov, to discuss “prospects of cooperation in the gas sector”. No details were released about the meeting and no deal has yet materialised. Because it is where the Central Asia–China pipeline originates, Turkmen involvement in a gas deal is necessary if Russia is to access the Chinese gas market—either directly, or via a swap, where Russian gas flows to Turkmenistan and more Turkmen gas flows to China.

But a deal with Turkmenistan is far from guaranteed. Russian gas transiting Turkmenistan risks crowding out expanding Turkmen production. And in a gas-swap scenario, Russian gas exported to Turkmenistan would need to be competitive with heavily subsidised domestic Turkmen gas, selling at low prices that would gain Russia little. Any deal may be small, granting only limited Russian access to the Central Asia–China pipeline or forcing Russian gas to be sold at low prices on the Turkmen market.

Construction costs associated with exporting gas via Central Asia would be smaller than the costs involved in building Power of Siberia 2, but some investment would still be required. Any large deal with Central Asia would require repurposing the aged and little used CAC pipeline for reverse flows. And while western Russian pipelines are dense, high-capacity and run close to or already interconnect with the CAC pipeline, many of them serve domestic markets and repurposing them to carry exports may be difficult.

If Russia both completes Power of Siberia 2 and finds a way to send gas through Central Asia, its pipeline capacity to export east from Western Siberia will begin to look like its pre-2022 Europe-facing gas infrastructure, providing 100–160bn m³/yr of export capacity. But to get that far, Russia must first conquer steep engineering and political challenges, and find the resources to invest tens of billions of dollars in infrastructure upgrades. GEI

Seth joined Gulf Energy Information in January 2023, where he researches LNG and pipeline projects for Global Energy Infrastructure, keeping GEI abreast of the newest projects and trends in gas infrastructure. Seth is a native of the DC area and a graduate of the University of Leeds.

Comments