Business Trends: China pushes shale gas drilling amid corporate shakeups

In what appears to be a move to increase domestic energy production and self-reliance, as well as boost competition among foreign companies, China is reorganizing its state-owned energy firms and widening the invitation to shale gas drillers.

Notably, the expansion in hydraulic fracturing operations in China will unfold as shale gas drilling in the U.S. takes a breath amid financial pressures and decreased drilling rates. The continued, reciprocal imposition of tariffs on exports, including energy, by the U.S. and Chinese governments will provide a colorful backdrop for this scenario.

Corporate shakeups amid trade war with U.S. Domestic energy giants China Petrochemical Corp. (Sinopec) and China National Petroleum Corp. (CNPC) are reorganizing their executive lineups, as announced in January. CNPC is the country’s largest oil and gas driller and natural gas importer, and is the parent of PetroChina Co. Sinopec is the world’s largest oil refiner by capacity and the parent of China Petroleum and Chemical Corp.

The chairman roles at Sinopec and CNPC, and the general manager role at CNPC, have been revised with some swapping of executives seen between the two companies and other domestic energy giants, such as China Shenhua Energy Co. The moves are hoped to bring stability and growth to PetroChina’s struggling refining and petrochemicals units, amid the country’s ongoing pipeline reform.

Additionally, energy tariffs will remain in place despite the trade deal struck by the U.S. and Chinese governments on January 15 for “phase one” negotiations. At the time of this publication, China’s tariffs on imports of crude oil (5%) and natural gas (25%) from the U.S. remain in full force. These tariffs mirror the U.S.’s $370 B in restrictions on imports of Chinese goods. These tariffs are likely to remain in place during the expected subsequent “phase two” negotiations of the deal.

China has, however, agreed to buy more energy from U.S. producers. Under the Phase 1 deal, the country will purchase additional energy exports from the U.S. worth $18.5 B in 2020 and another $33.9 B in 2021. The extra energy supplies include crude oil, natural gas, refined fuels, coal and others. The deal is a positive step for stalled LNG projects in the U.S. that had been eyeing purchase agreements from Chinese importers.

China’s energy hunger to worsen. China may need the extra gas, as it could overtake Japan as the world’s top LNG importer in 2022. The country is now the world’s largest importer of energy. After two decades of rapid industrial growth, China’s dependence on foreign oil supplies surged to nearly 75% in 2019 from around 50% in 2005.

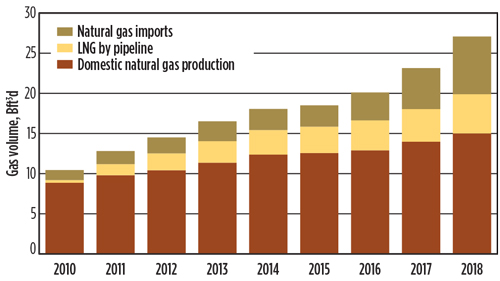

China also secured the top spot for natural gas imports in 2018 (Fig. 1), overtaking Japan as Chinese officials urged clean energy usage amid air pollution crises in its major cities. China’s reliance on foreign gas supplies is pegged at around 50% at present.

|

| Fig. 1. China’s natural gas production and imports, 2010–2018. Source: U.S. EIA. |

The Chinese government estimates that domestic gas consumption will expand by 10% in 2020, to 310 Bm3. The growth rate would represent a small slowdown from 2019’s 17.5% demand increase. However, China’s natural gas needs are anticipated to grow until at least 2050 as its population and industry continue to expand.

Policy shift entices foreign drillers. In an effort to offset its import dependence and boost its domestic energy output, China’s government announced in early January that it would open its upstream sector to foreign drillers this year. The news came after China released plans in December 2019 to spin off its oil and gas pipeline infrastructure into a new firm, a move intended to give companies better access to energy infrastructure.

Under the policy change, from May 1, foreign firms registered in China with net assets of CNY 300 MM ($43 MM) will be allowed to take part in oil and gas exploration and production. The policy will also apply to domestic companies that meet the same condition. Previously, international companies could enter the industry only through JVs or other tie-ups with Chinese firms.

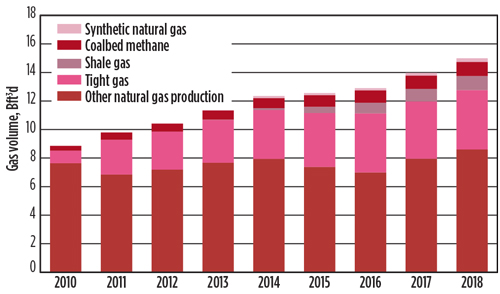

Natural gas production has grown in China (Fig. 2), largely because of increased development in low-permeability formations in the form of tight gas, shale gas and, to a lesser extent, coalbed methane. Output of unconventional gas accounted for 41% of China’s total domestic natural gas production in 2018.

|

| Fig. 2. China’s natural gas production by type, 2010–2018. Source: U.S. EIA. |

Increased production of both conventional and unconventional gas will be essential for China to meet its vigorous demand and reduce its import bill. It will also foster competition among foreign drillers, especially those working in shale and offshore gas. Officials in southwest Guizhou province have an ambitious plan to drill more than 80 new shale gas wells over the next 5 yr. These efforts are anticipated to result in production of 2 Bm3/yr by 2025.

Overall, China is on pace to double its natural gas output to 325 Bm3 by 2040 from 149 Bm3 in 2018. Key to achieving this goal will be the development of resource basins in southwestern Sichuan province (including shale and tight gas reserves), the northern Ordos basin and offshore (Fig. 3). China’s coalbed methane development is concentrated in the Ordos and Qinshui basins of Shanxi Province. These basins face significant challenges, including low well productivity and relatively high production costs.

|

| Fig. 3. Unconventional gas production in China by type. Source: U.S. EIA. |

Sichuan is a key development area for China’s infant shale gas sector and could represent as much as one-third of the country’s total gas production in the future, up from the present 20%, according to an August 2019 report by China’s National Energy Administration. PetroChina operates two fields in the southern part of Sichuan basin, and Sinopec operates one field in the eastern part of the basin.

In 2019 alone, PetroChina discovered shale gas reserves of more than 1 Tm3 in the Sichuan and northwest Tarim basins, collectively. The company produced an estimated 8.03 Bm3 of shale gas in Sichuan last year, an 88% increase from 2018. PetroChina and Sinopec’s combined shale gas output was forecast to reach 15 Bm3 in 2019.

Will China head the next shale gas revolution? China’s Academy of Engineering has forecast that China’s shale gas output could reach 280 Bm3, or 23% of the country’s total gas output, by 2035. This is despite technological, geological and financial challenges to shale gas drilling that could stunt China’s growth potential.

In 2018, the country produced approximately 10.9 Bm3 of shale gas, or less than 7% of the country’s total gas output. The projected rise in projected shale gas production would require more than 500 wells to be drilled per year from 2019–2035, or double the 2018 level. The government could, however, encourage expedited production of shale gas by waiving resource taxes on shale. Such a move would sweeten the government’s June 2019 extension of subsidies on domestic output of unconventional gas (including tight gas) to 2023.

Investments in shale gas by state-run firms have been meager thus far. Poor geology has made it difficult for Chinese producers to develop domestic shale reserves at a profit, without significant government support. For example, PetroChina’s internal rate of return (IRR) is only 8%–9% for wells in its largest shale find, the Changqing deposit in the Qingcheng field, despite efforts to drive down production costs. Such an IRR barely covers PetroChina’s own capital cost and is unlikely to attract foreign investors. By contrast, IRRs of 20%–40% are typical for U.S. domestic shale gas wells.

The vast volumes of water required to drill shale wells are also a concern, as water resources are limited in much of the shale-rich areas of mainland China. The country is estimated to hold 36.8 Tm3 of shale gas reserves—twice the reserves of the U.S. Drilling one shale well requires the injection of 10,000 m3 of water, and many wells must be drilled to justify the cost of output per well.

Furthermore, drilling interest from foreign producers has been limited by the low asset quality of China’s unclaimed resource deposits. Most of the shale “sweet spots” have already been taken by China’s state-run energy majors. An oversupply of natural gas worldwide has also beaten down gas prices, which could further serve to discourage drillers from taking the leap into China’s shale over the short term.

Despite these challenges, China’s decision to open up its shale basins to foreign drillers could encourage the establishment of needed technical and operations expertise when market conditions improve. It may also attract domestic independent companies, such as oilfield service providers, to join the game and help usher in a shale gas boom of China’s own. GP

Comments