Industry Trends: Five trends shaping the North American gas market to 2030

The shale revolution has changed the game for the North American natural gas market over the past decade. In 2008, North America was believed to be short of natural gas resources and in need of LNG imports. Now, 10 yr later, the region has transitioned to a gas exporter with LNG import terminals converting to exports, and new pipelines shipping gas to Mexico. This change was enabled by the meteoric rise of shale, accounting for more than 50% of total gas production.

Looking ahead to 2030, we expect North American gas demand to grow at 2%/yr, fueled by the attractiveness of US LNG exports and the retirement of coal power plants. On the supply side, we expect shale gas to continue dominating, with the Permian and Appalachian basins supplying approximately 55% of the North American gas market by 2030. The rapid development of shale could mean that more than $150 B of gas-related midstream investments will be needed by 2025 to enable abundant, inexpensive gas to reach demand centers. Overall, market conditions indicate that North American gas prices are expected to stay below $3/MMBtu for decades to come.

|

|

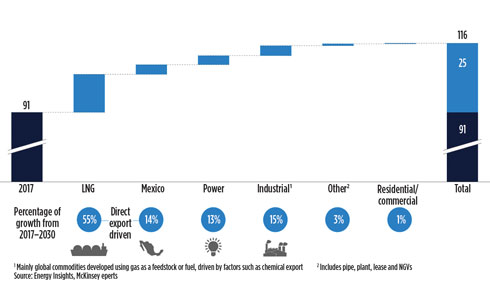

FIG. 1. North America gas demand growth by sector, Bft3d, 2017–2030. |

LNG will play a major role in supporting demand growth for North American gas, accounting for more than 50% of growth to 2030 (Fig. 1). As LNG is becoming increasingly important to global gas markets, the US has undergone extensive LNG terminal reconfiguration and construction to capitalize on the opportunity. The first LNG export cargo from the lower 48 states came from Cheniere Energy’s Sabine Pass terminal in 2016; today, LNG exports have grown to 3 Bft3d. At present, Sabine Pass and Dominion Energy’s Cove Point LNG terminal are in operation, while another four terminals (Cameron, Freeport, Elba Island, Corpus Christi) are under construction. By 2020, Wood Mackenzie expects a total of 10 Bft3d of capacity to come online, equivalent to 13% of total US domestic gas demand.

After the buildout of existing projects reaches final investment decision (FID), the taking of FIDs for new North American LNG projects is expected to be challenging over the medium term (2021–2024), mainly due to the global LNG market being oversupplied. However, the potential remains for attractive projects to take FID during this period if they can beat the global cost curve with high financial and operational efficiency.

Post-2024, depending on how Asian demand levels evolve, the global LNG market will begin to rebalance. US brownfield projects could be the first to come online, as pre-FID US projects are among the most attractive due to low CAPEX, outside of those in the Middle East. In its base case, Wood Mackenzie expects US LNG exports to grow to 16 Bft3d by 2030.

Coal use declines. In the near term, gas is expected to replace coal generation, although it will face competition from renewables over the long term. A total of 58 GW of coal-fired power capacity has been retired since 2010, representing 20% of existing coal capacity. This trend will continue, with another 26 GW of coal-fired power capacity to be retired soon. This leaves room for an anticipated 67 GW of new gas-fired capacity to fill the gap in power supply. Therefore, power demand for gas is expected to grow at 2%/yr until 2022.

Post-2025, as their economics become more favorable, renewables could compete with inexpensive combined-cycle gas plants, even without subsidies. This will encourage some power generation to switch from gas to renewables—solar, in particular. As a result, gas demand growth in the power sector is expected to slow to 0.3%/yr from 2022–2030 as renewables become more competitive, eventually accounting for approximately 21% of power generation by 2030. Nevertheless, gas will continue to play a crucial role in power generation from a reliability standpoint, if battery technology is not available at scale.

“Shale gale” in North America continues. North America has two major advantages when it comes to consistently producing plentiful and low-cost natural gas. First, technological improvements and increased efficiency have driven down breakeven prices for natural gas production in North America, making areas like the Marcellus and Utica more profitable. Thanks to pad drilling and advanced completion technologies, these two shale plays have seen new gas production per rig grow by a factor of 10 since 2008. By 2030, the Permian and Appalachian basins are anticipated to supply approximately 55% of the North American gas market, while production from the Marcellus and Utica shales is anticipated to account for approximately 40% of total North American gas supply (Fig. 2).

|

|

FIG. 2. North America natural gas production by basin, Bft3d. |

Second, the availability of associated gas also drives down costs. Given the recent surge in oil prices and increased drilling activity in the Permian, effectively zero-cost associated gas will flood the market and put downward pressure on gas prices. Associated gas is produced regardless of gas price levels, and its supply will increase by approximately 12 Bft3d from 2018–2030. Around 60% of this supply—equivalent to 15% of US gas production in 2030—will come from the Permian.

Midstream investments needed. More than $150 B of gas-related midstream investments will be needed to debottleneck and move shale gas from supply basins to demand centers by 2025. This newly produced shale gas will need somewhere to go, and existing takeaway capacity is inadequate for the increasing gas supply. Significant additional midstream infrastructure is necessary to move gas from the Permian and Appalachian basins to demand centers.

The Permian’s takeaway capacity is already constrained. Since gas is a byproduct of oil in the Permian, its production will rise along with oil prices regardless of in-basin gas prices. In response, the basin will need an additional 6 Bft3d of pre-FID pipeline capacity by 2025.

Alternatively, operators in the Marcellus and Utica shales are investing in regional projects like Atlantic Coast, Atlantic Sunrise, Mountain Valley and Nexus to debottleneck and move shale gas to the Midwest and Mid-Atlantic markets. Beyond these projects, pipelines with expanded capacity are needed to ship gas to the Gulf Coast to feed the LNG facilities. Consequently, more than $150 B will be needed in growth and maintenance CAPEX for gas pipelines and processing facilities over the next 7 yr. For example, large interstate pipeline projects alone account for approximately $35 B of Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) approval filings to come online in the next 5 yr. However, the probability of these coming to fruition will be dependent on how the regulatory landscape and regional policies develop.

|

|

FIG. 3. North America half-cycle breakeven price curve, $/MMBtu.1,2 |

North America can produce enough gas to meet 25-plus yr of demand at prices below $2.8/MMBtu. Expected coal plant retirements, increasing exports to Mexico and new LNG terminals coming online in the near term could help sustain a gas price of $2.50/MMBtu–$3.00/MMBtu. However, that is expected to change after 2020. The development of renewable energy and an oversupplied LNG market could mean slower growth on the demand side, while huge volumes of associated gas and debottlenecked Appalachian shale supply will flatten the cost curve from the supply side. Considering these factors, long-term gas prices below $2.80/MMBtu are likely (Fig. 3).

The outlook for the gas market in North America is complex. Although it is tempting to oversimplify and focus only on demand growth, many other factors are at play. Developments in shale, infrastructure and renewables will have lasting effects on North American gas production and prices. GP

|

Yasmine Zhu is a Senior Analyst with McKinsey Energy Insights, the market forecasting and analytics arm of McKinsey & Co.’s oil and gas practice. She joined McKinsey’s Houston, Texas office in 2015. Her expertise lies in North American natural gas economics, gas processing and midstream, LNG fundamentals and petrochemical asset valuation. Ms. Zhu holds an MS degree in chemical engineering from Stanford University in California and a BS degree in economics from Peking University in China.

Comments