Adapting traditional business models for an increasingly fragmented LNG industry

T. Shattuck and A. Slaughter, Deloitte Center for Energy Solutions, Deloitte Services LP, Houston, Texas

Since the 1960s, when LNG was first exported commercially from Algeria, natural gas trade via waterborne cryogenic cargoes has seen consistently strong growth. While much has changed in the last 50 yr, until recently the dominant commercial structures had hardly changed. The traditional integrated model—where major producers develop large and often otherwise stranded gas fields, build large natural gas liquefaction facilities and sell cargoes on long-term contracts to major utilities—has been remarkably stable.

However, over the last decade, global LNG trade has begun to incorporate a number of newer business models due to rapidly changing market dynamics, including increasing resource availability (e.g., US shale gas), new technologies [e.g., floating liquefaction (FLNG) and regasification (FSRU)] and new sources of demand (e.g., China and India).

While long-term contracts still comprise the bulk of current trade, spot and short-term volumes are now 30% of the market.1 New commercial arrangements are being used by portfolio companies, trading houses, tolling liquefiers, and smaller buyers and sellers, shifting how cargoes are bought and sold. The market is clearly changing.

To assess the scope and rate of this change, LNG market participants from around the world and across the value chain were surveyed, and industry leaders were interviewed. These views were consolidated with research from the authors’ organization to explore how companies can adapt to the rapidly evolving industry.

What is driving the change? In short, supply and demand patterns have changed significantly. Since 2010, volumes of LNG traded have increased more than 40% to roughly 320 metric MMtpy, with much of the new liquefaction capacity being developed in Australia and the US. At the same time, China (and to a lesser extent India) rapidly increased consumption of natural gas, largely supplied by LNG imports.1 In particular, the development of shale gas in North America, and the commercialization of offshore and coalbed methane in Australia, have rerouted LNG trade flows.

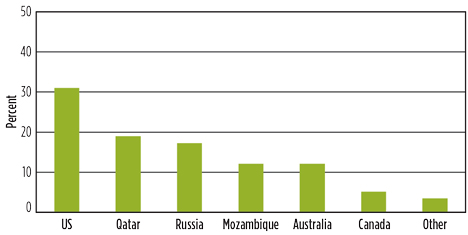

Looking to the future, survey respondents expect significant continued supply growth from the US, but Australia’s boom is expected to cool down with large-scale projects from Qatar, Russia and Mozambique on the horizon (Fig. 1). New supplies from Qatar will likely come from brownfield expansions of existing liquefaction facilities, but new capacity in both Russia and Mozambique will come from several large greenfield projects that are being considered for sanction. The US stands out, since expansions are being considered for a number of existing facilities, and more than 80 metric MMtpy of FERC-approved, yet-to-be-sanctioned liquefaction projects could be developed over the next decade.2

|

|

FIG. 1. Where will the majority of global liquefaction capacity be built in the next 5 yr? Source: Deloitte. |

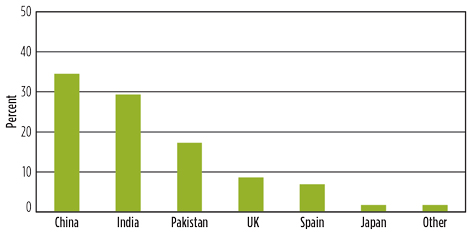

Similarly, survey respondents see LNG imports into China and India continuing to grow, while historically important importers like Japan, South Korea and Taiwan are expected to play smaller roles (Fig. 2). The latter will remain important, as they comprise nearly 50% of the market today; however, their growth will be more modest than developing economies elsewhere in Asia. This is likely driven by demographics and economic trends, as both China and India contain more than 1 B people each,3 and the former’s GDP has grown in excess of 6%/yr since the early 1990s.4

|

|

FIG. 2. Where will the majority of demand growth in absolute terms come from in the next 5 yr? Source: Deloitte. |

Additionally, environmental concerns may increasingly be at the forefront for many countries. For example, China’s push to reduce environmental emissions and dependence on coal seems to have led to a recent increase in natural gas imports, including LNG.5 Other countries heavily reliant on coal, such as India, might pursue a similar strategy. That could further tilt LNG demand growth toward developing rather than developed nations, as the latter often have better air quality.6

What challenges will companies face? As the LNG market evolves and becomes increasingly dynamic and diverse with more spot cargoes, more shipments to Asia, and more volumes exported from Australia and North America, a number of challenges are on the horizon.

To that end, respondents were asked about their views across a range of technological, financial and market questions. Three things stood out:

- Respondents overwhelmingly believe (76%) that spot and short-term contracts will grow faster than overall LNG trade. That could make it more difficult to build new capacity using project finance, as this has often been collateralized by traditional 20-yr contracts. Portfolio players and trading houses could fill the gap left by the absence of traditional offtakers. Additionally, future project development may be driven more by brownfield rather than greenfield, as the cost of the former is lower than the latter.

Respondents also suggested that producers and financiers might need to be willing to accept higher market risk, and potentially rely more on equity than debt. Equity financing, however, is likely limited to the largest players with access to sufficient capital to support these types of projects. It remains to be seen how other companies can commercialize large-scale projects using alternative financing structures. - US natural gas production has grown strongly, from approximately 55 Bft3d a decade ago to more than 80 Bft3d in 2018, and is projected to keep growing.7

This has facilitated significant LNG export growth—from essentially zero a few years ago to 3 Bft3d in 2018. Based on existing projects, exports could grow to more than 10 Bft3d in the next 5 yr, with much more unsanctioned capacity in the pipeline.8

The emergence of accessible natural gas supply with transparent pricing (e.g., Henry Hub) underpinned a new business model built on tolling agreements rather than on traditional oil-linked offtake contracts. This style of contract tends to provide flexibility to the buyer, allowing them to procure their own natural gas and decouple LNG prices from liquids pricing (e.g., Brent or Japanese Customs-cleared crude).

However, less than 20% of respondents think that companies could develop US-style tolling projects elsewhere. They cited a range of reasons, including regulatory, market and project scale challenges. However, countries like Australia and Canada have large unconventional gas resources, which could underpin tolling-style agreements for future projects. Even absent international tolling projects, the existence of contracts with more flexible destination and pricing terms means that even traditionally developed projects will likely need to rethink how they deliver gas to the market. This could exacerbate challenges posed by fewer long-term contracts. - As the number of buyers increases in the developing world, new buyers may have more challenging credit ratings than traditional buyers, resulting in greater counter-party credit risk. Moreover, even as total volumes traded increases, the average cargo size could decrease as companies export to smaller end-use markets. That means small-scale, modular and floating projects will likely become increasingly important to offset new commercial risks not seen with larger, more traditional buyers.

It also means that the need could arise for improved logistics as the number of trading partners and vessels proliferate, likely requiring new technologies to be deployed. The Internet of Things, blockchain and advanced data analytics all come to mind; however, the industry appears to be unsure about how to best adapt and deploy new technologies. Roughly 60% of respondents say that digitalization could have an impact on the LNG industry, with a particular interest in deploying blockchain to facilitate trade. Execution will be due to both technical complexity and difficulty in generating consensus around a single system. Organizations such as VAKT have developed pilot projects to provide a digital ecosystem to support oil and gas trading using blockchain, but adoption has not been seen at scale.9

How can companies adapt? Recent trends could create obstacles for traditional business models, and novel strategies have yet to be proven resilient at scale. Companies will need to overcome these challenges to meet growing demand for energy, including LNG, driven by economic and population growth around the world, particularly in Asia.

The world seeks flexibly provided gas on a short-term basis, at prices competitive with other sources and other fuels. That will require the economies of scale of a larger traditional project, with the scalability of a new, smaller project and the balance sheet of a major portfolio player. Few new projects meet these criteria—almost certainly not enough to meet future consumption.

How can producers square the circle? Technology can play a role. For example, modular liquefaction can provide attractive unit costs even with smaller upfront per-metric-MMtpy commitments from both buyers and sellers. Similarly, as FLNG becomes more widespread, costs should decline as technology matures, opening up opportunities to commercialize smaller offshore gas fields.

Moreover, with the proliferation of contract types, trading houses could buy long across a number of price markers and contract durations, and use the increasingly liquid markets with more transparent pricing to hedge short-term risks. The two combined can help developers sanction with less onerous financing terms, despite the lack of anchor offtakers that would buy gas long term for their own consumption.

Similarly, the development of true gas-on-gas LNG markets, combined with improved cargo trackability and dispatchability (e.g., using a shared database or blockchain-based system), could reduce the perceived risk of uncontracted liquefaction volumes. If excess capacity could be more transparently priced, then LNG developers could access alternative funding outside of project finance, as untapped residual value could emerge. This could lower equity requirements for project developers, even if buyers are less credit-worthy or seeking shorter contracts.

The next 5 yr could be pivotal as LNG producers, traders and buyers navigate evolving markets and change obstacles into opportunities. Technology alone may not overcome barriers, but together with business models, companies can adapt as the market changes. GP

Note

This article is an excerpt summary of Deloitte’s March 2019 report “Remodel, reinvent: How technology and changing business models are impacting the future of LNG.”

Literature cited

- International Gas Union, “2019 world LNG report,” April 2, 2019, online: www.igu.org/sites/default/files/node-news_item-field_file/IGU%20Annual%20Report%202019_23%20loresfinal.pdf

- US Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, “North American LNG export terminals approved, not yet built,” online: www.ferc.gov/industries/gas/indus-act/lng/lng-approved-export-new.pdf

- US Central Intelligence Agency, “Country comparison: Population,” CIA World Factbook, online: www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/335rank.html

- World Bank, “Chinese annual GDP growth,” online: data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?locations=CN

- Sugiura, E., “China on pace to become top natural gas importer in 2018,” Nikkei Asian Review, October 14, 2018, online: asia.nikkei.com/Business/Markets/Commodities/China-on-pace-to-become-top-natural-gas-importer-in-2018

- Foley, K. E., “Every country has terrible air pollution, but these are the world’s worst,” Quartz, September 28, 2016, online: qz.com/794542/air-pollution-map-by-country-fine-particulate-matter

- US Energy Information Administration, “US dry natural gas production,” online: www.eia.gov/dnav/ng/hist/n9070us2m.htm

- US Energy Information Administration, “Annual energy outlook 2018,” February 6, 2018, online: www.eia.gov/outlooks/aeo

- VAKT, online: www.vakt.com

|

Thomas Shattuck is a Lead Analyst for Deloitte Services LP’s Center for Energy Solutions, analyzing trends in the global energy industry with a focus on LNG, upstream exploration and development, as well as global energy demand. Prior to joining Deloitte, he worked as a market researcher covering deepwater and frontier oil and gas projects in North America. Mr. Shattuck started his career as a field engineer for a leading oilfield services company in the Gulf of Mexico.

|

Andrew Slaughter is the Executive Director for the Deloitte Center for Energy Solutions, Deloitte Services LP. He works closely with Deloitte’s Energy, Resources and Industrials leadership to define, implement and manage the execution of the Center’s strategy; develop and drive energy research initiatives; and manage the development of the Center’s eminence and thought leadership. During his 25-yr career as an oil and gas leader, he occupied senior roles in major oil, gas and chemicals companies and consulting/advisory firms.

Comments