Key contributing factors to safety incidents at gas processing facilities

N. Behari, Shell Canada Ltd., Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Companies too often cite human factors and equipment malfunctions as the root causes of accidents at gas processing facilities. However, extensive research reveals one commonly overlooked factor at play—the lack of a well-defined process safety culture, especially regarding human errors and interaction.

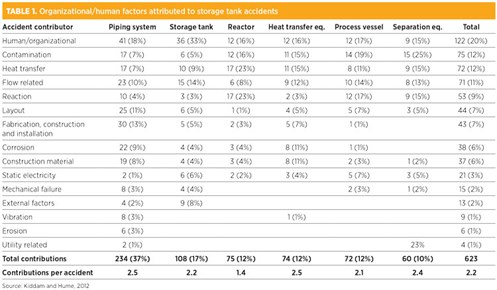

Extensive study of the maturity of a facility’s process safety culture as it relates to all human factors provides a clearer and more comprehensive explanation for some major, and even catastrophic, incidents at several plants. As an example, note the percentage of human errors at a storage tank facility compared with the total percentages of other causes in Table 1.

|

While safety audits may indicate that existing process safety management (PSM) systems are effective, a study of plant observation audits shows a significantly different picture. One example is employee behavior, which theoretically should be governed by the existing safety culture. Yet, the reality reflects an absence of employee and management commitment to safety management systems. Flaws are demonstrated by incidents of employee failure to apply the appropriate safety behavior while operating equipment, ineffective management oversight of maintenance, and inadequate operator training.

Process safety culture assessments in the energy sector. To verify the importance of a mature process safety culture, it was important to conduct a series of assessments in the gas processing industry. One of them—a gas company consisting of 1,100 full-time employees and 1,000 sub-contractor employees that provides GTL services, ammonia processing, utilities and fuel dispensing—was assessed for process safety culture maturity.

Despite having process safety in place for several years, certain elements did not include a solid emphasis on US Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) PSM standards. The need for PSM implementation arose due to numerous incidents that occurred in the global petrochemical sector that resulted in fires, explosions and toxic releases.

Process safety audits are designed to evaluate the effectiveness of the PSM system. However, plant observation audits indicated that employees at the facility did not display the correct process safety behaviors. In most instances, the audit found that employees who neglected to maintain equipment or worked without using proper operating procedures had not been provided with adequate operator training. The audit found that active employee participation and management commitment were lacking in selected plants, and that methods needed to be developed to improve process safety culture.

Interviews with employees in the previous decade verified the existence of the problem. They reported feeling burdened by process safety because they considered it unnecessary extra work. The launches of a revised permit to work and management-of-change systems were supposed to enable employees to work safely and become more aware of risk coverage before work was executed, yet the resulting work planning and scheduling process took longer. Resistance to change was reported due to inadequate staff and inappropriate work behavior. The compilation and execution of standard operating procedures and the updating of process safety information represent other aspects of process safety that were inadequately implemented.

During the onsite human factors interviews, older employees reported feeling comfortable with remembering everything by rote, whereas new or junior employees did not appear to fully understand process safety or plant processes. The latter group may not have had access to operating procedures and was either incapable of making knowledge-based decisions or was inadequately trained.

The human factors interview feedback indicated that accident risk at these plants was likely to increase due to a low level of safety culture maturity and human factors deficiencies, both of which placed the company at risk for repeat process safety incidents.

Quantifying human factors. The UK’s Health and Safety Executive (HSE), the regulator responsible for workplace health, safety and occupational risk research, developed a Human Factors Inspectors’ Toolkit to help identify human-related weak spots and incorrect human behavior in process safety. The toolkit is divided into three levels:

- Core topics fundamental to human factors, such as their role in accident investigations and specific human failure

- Common topics, including safety response and effective communications

- Specific topics that include alarm handling, fatigue risks and analysis of process safety culture.

Although created in the UK, the toolkit has been customized to comply with US OSHA and Canadian regulations and is easily applied in any gas processing company in the two countries.

Certain human factors criteria can be addressed from the toolkit and onsite process safety audits, but human- and behavioral-related issues are investigated by conducting interviews with front-line employees. The audit findings and associated interview questions address human factors deficiencies and recommendations for corrective actions that need to be implemented—the very factors integral to a mature process safety culture.

PSM implementation is designed to mitigate large-scale, catastrophic incidents causing multiple loss of life and major asset or reputation damage due to inadvertent fire, explosion or toxic release, which occur infrequently. To implement PSM, many organizations (including Sasol, Shell, BP, ExxonMobil and others) make use of an HSE policy that defines management’s commitment to process safety.

On the other hand, employee participation, change management, safety campaigns and selected process safety compliance audits address behavioral safety requirements and the degree of safety management system compliance, respectively. The components of human factors are integrated into each process safety element standard. They can be used to assess the safety maturity culture, in addition to identifying high-level risks and blind spots that prevent the organization from institutionalizing and sustaining process safety.

Assessing the safety maturity culture through human factors identifies high-risk process safety deficiencies that interface with the organization, employees and operational job requirements. However, the more important questions to be resolved are:

- Can safety culture and maturity be effectively assessed through multidisciplinary concepts related to human factors and team leadership behaviors?

- What impact does safety culture through human factor dimensions have on enabling sustainable PSM?

The answers will help identify the organizational safety maturity stages, provide effective risk-based decision-making and aid in long-term, robust process safety strategy development and implementation.

The human factors study is a central theme in process safety culture maturity and effective business performance. Safety culture maturity models indicate drivers of key human factors dimensions (e.g., degree of process safety sustainability, continuous improvement, incident reduction and reporting effectiveness) and include assessment of employee team leadership behaviors.

The human factors assessment relates employee behavior and job roles within the organization to determine safety culture maturity. The purpose is to identify risks associated with human factors and provide preventive and corrective actions. The assessment allows plant management and operational teams to develop appropriate safety leadership behaviors that are necessary to sustain process safety, lower incident rates, create a learning culture and increase organizational safety maturity.

Researching human factors and mature safety culture. The list of questions for researching this topic came from several sources; however, to avoid duplication with similar questions contained in OSHA safety audit protocols, new questions were added to address the implementation and sustainability of process safety customized for the energy sector.

The human factors interview questions were selected strictly based on human-machine interfaces, safety management systems (including organizational communication), learning and safety culture. Topic classifications for these interviews covered the breadth of the gas processing industry, which included (but were not limited to) maintenance error, alarm handling, process control, procedures and remote operations communications.

Structured interviews were conducted anonymously with operator staff from each department, with feedback provided to their managers. A “no name, no blame” philosophy was encouraged to elicit honest feedback from employees. The aim was to compare the safety culture attributes and human factors of different plants, including GTL and ammonia, to identify improvement gaps and best practices associated with successful and sustained process safety implementation.

The results from the interviews were consolidated to identify common themes using a SWOT (strength, weaknesses, opportunities and threats) analysis. High-level risks that could potentially undermine the safety culture maturity throughout the organization were identified. These common themes, which were used to measure the level of safety culture maturity, help identify the path forward.

Previous interviews and second-party safety audits indicated that employees prefer to “market their plants” and may provide information that could be misleading or unsubstantiated by fact or documentation. A qualitative analysis conducted on process safety audit results and findings, FER-SI (fire, explosions, releases severity index) trends and perception surveys would, therefore, support or deny any claims made by operators during the human factors interview assessment.

Team leadership behaviors are investigated to identify potential limiting behavior that may undermine the safety culture maturity in each department, in addition to assessing audit scores and FER-SI trends. Process safety audit scoring provides an indication of how well the plant is implementing or sustaining process safety, and selected individual scores per element are linked to human factors concerns and issues. FER-SI trends and reporting frequency can be associated with human factors pertaining to organizational incident learning, continuous improvement and leadership behaviors undermining or encouraging effective reporting. Findings from the qualitative analysis can be used to assess present and future safety culture maturity levels and to propose solutions to eliminate human factors-related risks.

Safety incidents and their relation to culture. The absence of a mature process safety culture was apparent as a contributing cause for several major accidents, which include the fire at Kings Cross, the Chernobyl nuclear radiation explosion, the Piper Alpha explosion, the BP Texas City refinery explosion, the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico and the nuclear accident resulting from the Fukushima earthquake.

A close examination of several of these incidents, all of them catastrophic, reveals the extent to which the lack of a mature culture possibly played a role. The 1987 Kings Cross flash fire in the London Underground, for example, claimed the lives of 31 people and left nearly 100 injured. An investigation showed there was nothing in the safety culture of the London Underground that addressed the possibility of a flash fire because none had occurred in the history of that subway. Ironically, the cause of the blaze was determined to be the seemingly innocuous act of discarding a cigarette on an escalator. Tragically, the escalator was constructed of wood.

The 2005 explosion at the BP refinery at Texas City is another example of the costly consequences of a failed safety culture. Company investigators attributed the cause of the blast as “heavier-than-air hydrocarbon vapors combusting after coming into contact with an ignition source, possibly a running vehicle engine.”

Could the culture have helped prevent this explosion that killed 15 people? Based on the findings of the US Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board (CSB), the answer is yes. In its list of causes, the CSB included a failure of company oversight of safety culture and accident prevention. BP has since upgraded its commitment to PSM significantly in line with HSE requirements.

As these episodes proved, the presence of a mature process safety culture integrated with an effective safety management system is paramount to prevent catastrophic incidents. Studies in the UK and Canada have established maturity levels through which organizations can evaluate the level of growth of their safety cultures. These maturity levels are outlined in the following sections.

Level one: Emerging. Safety is defined by technical and procedural solutions and compliance with regulations. Safety is not seen as a key business risk, and the safety department is perceived to have primary responsibility for safety. Many accidents are viewed as unavoidable and as “part of the job.” Most front-line staff are uninterested in safety and may only use safety as the basis for other arguments, such as changes in shift systems.

Level two: Managing. At this level, the organization’s accident rate is average for its industrial sector, but there tend to be more serious accidents than average. Safety is viewed as a business risk, and management puts time and effort into accident prevention. Safety is solely defined in terms of adherence to rules and procedures and engineering controls. Accidents are viewed as preventable. Managers perceive that the sole cause of most accidents is unsafe behavior of front-line staff. Safety performance is measured in terms of lagging indicators, such as lost time injuries (LTI) with safety incentives based on reduced LTI rates. Senior managers are reactive in their involvement in health and safety (i.e., they use punishment when accident rates increase).

Level three: Involving. Here, accident rates are relatively low, but they have reached a plateau. The organization is convinced the involvement of the front-line employee in health and safety is critical for future improvements. Managers recognize that a wide range of factors cause accidents and that the root causes often originate from management decisions. Many front-line employees are willing to work with management to improve health and safety. Most staff accept personal responsibility for their own health and safety. Safety performance is actively monitored, and the data is used effectively.

Level four: Cooperating. Most staff are convinced that health and safety are important for both moral and economic reasons. Managers and front-line staff recognize that a wide range of factors cause accidents, and the root causes are likely to involve previous management decisions. Front-line staff accept personal responsibility for everyone’s health and safety. The importance of all employees feeling valued and treated fairly is recognized. The organization puts significant effort into proactive measures to prevent accidents. Safety performance is actively monitored using all available data. Non-work accidents are also monitored, and a healthy lifestyle

is promoted.

Level five: Continuous improvement. In a perfect world, every company or organization would perform at this level. Prevention of all injuries or harm to employees (both at work and at home) is a core company value. The organization has sustained a period of years without a recordable accident or high-potential incident, but there is no feeling of complacency. It understands that the next accident is just around the corner. The organization applies a range of indicators to monitor performance but is not performance-driven, because it has confidence in its safety processes. It constantly strives to be better and improve hazard control mechanisms. All employees share the belief that health and safety are a critical aspect of their jobs and accept that the prevention of non-work injuries is important. The company invests considerable effort in promoting health and safety at home.

A mature safety culture requires a call to action. Corporations need to create mechanisms to enable process safety maturity to move toward the continuous improvement and organizational learning supported by interdependent team leadership. Some of these enablers could include the rotation or transfer of employees to other plants so that the upward safety maturity mobilization can be accelerated. Both safety and plant employees can be transferred so that safety blind spot risks are removed, and continuous improvement is encouraged in all plants.

Development of a continually evolving safety improvement plan (SIP) is encouraged, along with a management commitment to provide a safety leadership psychologist in each facility as the plan is implemented. The psychologist can coach plant managements on effective facilitation skills. In addition, all managers undergo procedural training to increase or refresh their operational knowledge and human critical task analysis training to understand various failure modes in human reliability.

Process safety needs to evolve with the company. Sustainability through effective leadership is the key driver for improving human factors dimensions and accelerating organizational safety culture maturity. Leadership interventions regarding safety behavior are essential if management is to commit to process safety and to create an organizational shift where front-line employees, production supervisors and operations managers are responsible for sustaining process safety. GP

Note

The views expressed in this article are the author’s, and may not represent those of the author’s employer.

|

NIRESH BEHARI is a process safety engineer in the petrochemical and explosives sectors. For more than 20 yr, he has developed, implemented and managed safety management systems for Fortune 500 companies that were required to comply with OSHA’s Process Safety Management Standard and EPA’s Risk Management Plan Rule. His positions have included Operational and Turnkey Engineering Manager and Process Safety Lead, as well as HSE manager. Mr. Behari recently published a research textbook on process safety culture in the energy sector.

Comments