Mexico’s continuing energy reform feeds pipeline, LNG aspirations

The global energy industry has witnessed how the shale boom turned the US into a leading gas producer and exporter. Many of the recent developments in the natural gas/LNG sectors of the Americas have been concentrated in the US Gulf Coast region, which is a key energy hub for much of the world. But what about Mexico?

Mexico is in the midst of an energy revolution, although it has not yet established many natural gas or LNG projects. The country has ample shale gas resources—the sixth-largest in the world, according to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA)—but limited production. However, due to energy reforms over the past few years, Mexico has opened itself to new developments and investment opportunities that can help meet growing demand. The potential exists, but questions remain:

- What is the present state of the natural gas/LNG sector in Mexico?

- What projects are under development or planned?

- What is the likelihood of these projects being completed?

- Most importantly, of what key factors should the industry be aware?

Mexico’s energy reform. On December 20, 2013, Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto formally signed one of the most significant economic reforms in the country’s existence—one that required an amendment to the country’s constitution.

With that reform, Mexico effectively opened up its oil and gas market to private foreign and local investors for the first time since 1938. The legislation ended the 75-yr state monopoly of Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) in the local oil and gas sector.

Since 2013, a number of key additions and updates have taken place with regard to Mexico’s energy reform. The overall purpose has been to attract private capital and technical expertise to build the Mexican energy industry, maximize oil and gas revenues, and boost economic growth through 2025. These initiatives were spurred by strong growth in demand, falling production and the country’s evolving energy needs in areas such as refining technology and infrastructure.

Nearly 5 yr have passed since the energy reform was introduced. Much of the resulting investment has been tied solely to oil and gas exploration. So, why has the country not seen an influx of investment and projects for natural gas and LNG? A few contributing factors include the structure of the reform, the restructuring of government entities and the pace of implementation of the reform. Common factors, such as risk and uncertainty, are also present. The reforms were implemented just prior to the mid-decade crash in crude oil and natural gas prices, which also came as a setback.

More than 10 yr have passed since NYMEX natural gas futures were higher than $13/MMBtu (Fig. 1). After the global economy and markets crashed across the board in 2008, natural gas began to gradually move up, eventually climbing above $5/MMBtu in early 2014.

|

| FIG. 1. Natural gas futures prices, 1994–2017. Source: US EIA. |

|

| FIG. 2. North American natural gas production, 2015–2016. Source: Energy Web Atlas. |

This momentum was short-lived, as energy prices, including natural gas futures, plummeted again and fell below $2/MMBtu at times during 2015 and 2016. The market has not risen above $4/MMBtu since December 2014. This market uncertainty has left many companies unwilling to take a risk on long-term projects within Mexico’s energy sector.

Mexico’s natural gas/LNG industry. The country has limited natural gas production, forcing it to rely heavily on pipeline gas imports from the US, and on LNG imports from other countries. According to the US EIA, US gas exports to Mexico have nearly quadrupled in the past decade, reaching approximately 1.4 Tft3 in 2016. Mexico is investing more than $10 B in the construction of additional pipelines to feed US gas into the country.

The imports will be used to generate power for the country’s central and northern cities. The country must also work to develop its abundant shale gas resources, which are the sixth-largest in the world at 545 Tft3, according to the US EIA.

Mexico is a major consumer of natural gas, but it is not a large producer. The country typically produces less than 100 Bm3 of gas, which is fed to its 11 natural gas processing plants with a combined capacity of approximately 6 Bft3d. By contrast, the US has more than 600 natural gas plants. The data highlighted in Figs. 2 and 3 show typical natural gas production and consumption levels, respectively, for North American countries. These average production volumes are not expected to vary significantly over the long term. Fig. 4 shows LNG consumption volumes in the US and Mexico in 2016.

|

| FIG. 3. North American natural gas consumption, 2015–2016. Source: Energy Web Atlas. |

|

| FIG. 4. US and Mexico natural gas LNG consumption, 2016. Source: Energy Web Atlas. |

Demand is expected to be even greater within the next 12 yr. Mexico’s natural energy ministry, SENER, announced that approximately 14.7 GW of new gas-fired power generation will begin operation by 2020. Gas is Mexico’s largest source of electricity generation, accounting for a little more than 50%. According to SENER, more than 60% of Mexico’s electric capacity additions from 2016–2020 will come from gas-fired power plants. SENER also forecasts that Mexico’s natural gas demand will increase from 3.6 Bft3d in 2015 to 5.4 Bft3d in 2029 (Fig. 5). The construction of additional gas pipelines will provide Mexico with ample, cheap feedstock for much-needed power generation (Fig. 6).

|

| FIG. 5. Cumulative projected power generation capacity additions in Mexico by fuel type, 2015–2029. Source: US EIA. |

|

| FIG. 6. Mexico projected natural gas consumption in the power generation sector, 2015–2029. Source: US EIA. |

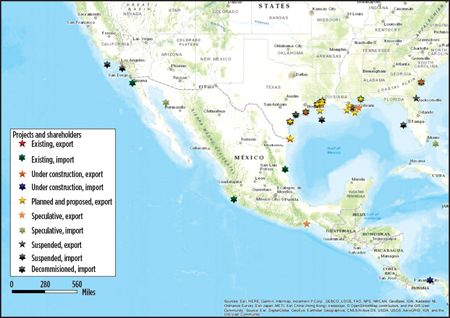

Existing and proposed LNG projects. Five LNG projects are located in Mexico. Three LNG import projects have already been built and are in operation. Two LNG export projects have been proposed, but are still speculative at this point (Fig. 7).

|

| FIG. 7. Map of Mexico’s LNG projects. Source: Energy Web Atlas. |

|

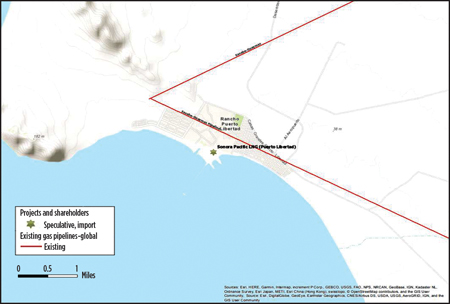

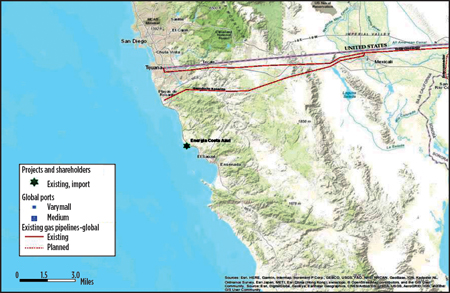

| FIG. 8. Sonora Pacific LNG project proposed location. Source: Energy Web Atlas. |

However, in taking a closer look at the LNG projects that are already in operation (Table 1), it can be seen that these three projects—Energía Costa Azul, Manzanillo and Terminal de LNG de Altamira, which have a total combined capacity of just under 15 Mtpy—were started well before Mexico’s energy reform was enacted. Due to the growing volume of pipeline imports from the US, these three regasification terminals are under-utilized.

In the meantime, the two LNG export projects that are still in the proposal phase (Table 2) are expected to add more than 12.1 Mtpy if they reach completion. The Sonora Pacific LNG project (Fig. 8) is anticipated to start by 2022. It was first announced in May 2004 by Houston-based DKRW Energy LLC, and later placed on hold in March 2011 because low natural gas prices in the US at that time made it more attractive for Mexico to import gas via pipeline rather than landing LNG cargoes for regasification. The project was close to being abandoned until Houston-based Aecom Capital took an equity stake in the project in October 2017. Preconstruction work is still in progress, but no timeline has been set for the start of construction. The project would provide LNG to Mexican, South American, Central American and Pacific Basin markets.

|

Overall, the Sonora LNG project appears to have a better chance at getting off the ground than does the Pacific LNG project (Fig. 9). The project would deploy a Golar-owned-and-operated FLNG storage and production unit to convert Mexican feed gas to LNG for export to Pacific markets. The unit is planned to produce approximately 2.2 Mtpy.

The Pacific LNG project is unique in that it is the only standalone LNG export project proposed for Mexico. The FLNG vessel was originally expected to be completed and operational by mid-2018, but at the time of publication, it has not yet moved into the construction phase. Outside of the company’s initial press release, no news of development on the Pacific LNG project has been released.

Another issue that makes the Pacific LNG project unlikely is the lack of pipeline connections to the proposed offshore location near Salina Cruz. Fig. 9 shows only one existing pipeline near the offshore LNG project, and two pipelines that are still in the planning phase.

One recently announced LNG export project that may have a better chance at being developed is Mexico’s existing Energia Costa Azul LNG import terminal (Fig. 10). In February 2018, Sempra-owned Infraestructura Energética Nova (IEnova) said it had made “significant progress” on a project to convert the Energía Costa Azul LNG terminal to a liquefaction facility for export to Pacific markets. Should the project go according to plan, it could come online by 2022 or 2023.

|

| FIG. 9. Pacific LNG project proposed location. Source: Energy Web Atlas. |

|

| FIG. 10. Proposed location for the Energia Costa Azul LNG project. Source: Energy Web Atlas. |

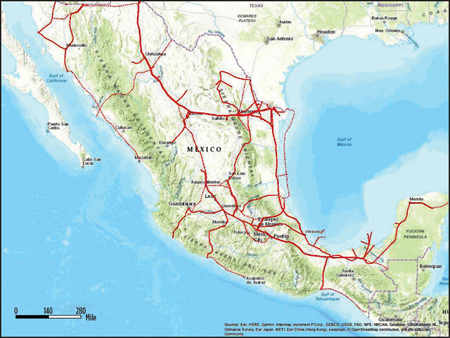

Existing and planned pipelines. Mexico has a well-established pipeline network for crude oil, refined products, petrochemicals and natural gas. In combination with strong demand, this existing and well-developed infrastructure has made it easier for some US-based companies to develop cross-border pipelines between the US and Mexico.

Mexico has 67 existing natural gas pipelines, and another 30 are in the planning phase. Among those 30 in the planning phase, eight are international pipelines. The remaining 22 are domestic.

The main objective of Mexico’s 5-yr plan (2015–2019) for the expansion of its natural gas transport and storage system is the construction of 13 gas pipelines (Fig. 11), most of which were commissioned by the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE) to feed Mexico’s thermoelectric power plants.

|

| FIG. 11. Mexico’s existing pipeline network. Source: Energy Web Atlas. |

This master plan has three main objectives:

- Increase and diversify the supply capacity of imported natural gas to northern and central areas of the country to compensate for supply fluctuations from southern Mexico.

- Achieve redundancy to help alleviate congestion in the system and meet demand for the central and western portions of the country.

- Extend coverage of the country’s natural gas transportation system to open new markets and help contribute to future national economic development.

Moving in the right direction. This past year, Mexico has taken some key steps toward improving its energy infrastructure and its relationship with the global energy industry. These steps include an expansion of the country’s participation in global energy discussions, an auction of assets, the establishment of a gas pricing system and further infrastructure development.

International relations. Mexico has already committed to taking an active role in the industry by joining the International Energy Agency (IEA) in February. The country became the 30th member country and the first Latin American country to join the Agency.

Continued auction of assets. Mexico’s technically recoverable shale gas resources are the sixth-largest in the world, at an estimated 545 Tft3. The country also has an estimated 17 Tft3 of proven natural gas reserves.

|

| FIG. 12. Hydrocarbon basins in Mexico. Source: IEA. |

Among the key plays (Fig. 12) are the Eagle Ford Shale of the Burgos Basin, which extends south from Texas into northern Mexico and holds an estimated 343 Tft3 of recoverable shale gas and 6.3 Bbbl of shale oil resource potential.

Other plays include the Sabinas Basin, with an estimated 124 Tft3 of recoverable shale gas resources within the Eagle Ford and La Casita shales. The Tampico, Tuxpan and Veracruz basins add 28 Tft3 and 6.8 Bbbl of technically recoverable shale gas and shale oil potential from the Cretaceous and Jurassic marine shales.

In July 2017, SENER opened the onshore portion of the Burgos basin for natural gas exploration and development by private companies. This marked the first time non-state entities were offered access to the Burgos basin.

Even more noteworthy, on September 5, 2018, Mexico will hold its first bidding award for unconventionals—nine blocks of gas. The National Hydrocarbons Commission (CNH) announced the first unconventional bid round on March 1, 2018. The nine blocks are located in the Burgos region in Tamaulipas, with conventional prospective resources of approximately 53 MMboe and unconventional prospective resources of approximately 1,161 MMboe.

Market developments. In the meantime, Mexico has committed to developing a market for its natural gas industry. In August 2017, CRE published, for the first time, its National Reference Index for Natural Gas Wholesale Prices. The index, referred to as IPGN, is based on the average price of transactions made by shippers across the entire country.

Also in March, CRE began publishing its first regional monthly reference price indexes. The six regions are:

- Region 1: Baja California, Sinaloa and Sonora

- Region 2: Coahuila, Chihuahua and Durango

- Region 3: Nuevo Leon and Tamaulipas

- Region 4: Aguascalientes, Colima, Jalisco and Zacatecas

- Region 5: Mexico City, State of Mexico, Guanajuato, Guerrero, Hidalgo, Michoacán, Morelos, Puebla, Querétaro, San Luis Potosi and Tlaxcala

- Region 6: Campeche, Chiapas, Oaxca, Quintana Roo, Tabasco, Veracruz and Yucatán.

In addition, CRE aims to establish forward-looking price indices in an effort to further develop the futures market. However, these CRE indexes are intended to be indicative and temporary. The expectation is that the CRE will cease publication once the market is able to develop indices on its own.

Continued infrastructure development. A missing component of Mexico’s energy infrastructure is storage. At present, no underground gas storage exists in Mexico. However, a plan is in place to develop natural gas storage capacity by launching a series of tenders for storage capacity later this year. In a draft policy released in December 2017, Cenagas will be required to keep at least 45 Bft3 (1.26 Bm3) of gas in storage by 2025, representing 5 d of domestic consumption.

A rise in storage capacity would allow domestically produced gas to better compete with LNG imports, thereby strengthening Mexico’s energy security. Cenagas has identified potential storage sites at 15 fields, with estimated reserves of 2.13 Tft3.

Potential roadblocks to energy buildout. Change within a country’s energy sector is usually not an overnight phenomenon. As such, the transformation of Mexico’s natural gas and LNG assets face political, economic and environmental challenges.

Political implications. The relationship between the US and Mexico has grown in terms of oil and natural gas trade. However, tensions between both countries have been front and center over the past year with President Trump in office. Since his presidential campaign, Trump has sought to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), or remove it altogether. However, his stance on NAFTA has softened recently, and all of North America is keeping an eye on the trilateral discussions.

With regard to the energy industry, NAFTA basically eliminated tariffs for crude oil, gasoline, motor fuel blendstock, distillate fuel oil and kerosine-type jet fuel. Should talks for NAFTA break down, many in the industry have speculated on the impact it may have on projects in development.

The move to renegotiate NAFTA comes as Mexico is in the midst of a presidential election. In July, Mexican voters will elect a new president, replacing the incumbent Enrique Peña Nieto. Among the candidates, leftist leader Andrés Manuel López Obrador has already raised skepticism with a $6 B–$10 B plan to build new refineries.

In addition to the refinery plan, Obrador has mentioned reviewing and possibly revoking Mexico’s energy reforms, should he win the elections this July. The construction of new refineries is highly unlikely, however, as Mexico’s refineries are already operating at less than half of their crude processing capacity. Also, Obrador would need to clear a majority vote among his fellow politicians before reversing any energy reforms.

Market factors. Mexico will continue to tap into the abundance of US gas supply to meet demand. One restriction to this, however, is the capacity flow into Mexico. If Mexico’s demand does indeed grow as expected, the question remains if the country’s existing pipeline infrastructure will be able to handle the growing influx of imports from the US.

As discussed previously, Mexico is expected to add to its existing pipeline network; however, as with any project timeline, this may change due to legal, environmental and financial issues. Any significant delay in these pipeline projects could impact the development of the market.

A major market factor that has brought buyers and sellers to a stalemate is supply contracts. Countries purchasing LNG typically want smaller volumes and more flexible contracts, while companies exporting and selling LNG want larger volumes and longer commitments. These long-term commitments are key to developing LNG projects. A lack of supply contracts can effectively put an end to any LNG project under development.

Environmental/territorial factors. Mexico’s opening of its energy industry has succeeded in attracting interest and capital, but it has also drawn the ire of environmental and indigenous groups.One such example is from 2017, when Sempra Energy’s $400-MM natural gas pipeline in northwest Mexico was disabled by protesters. The pipeline was part of a network that was planned to carry gas from Arizona more than 500 mi to Mexico’s Pacific coast.

Situations like this have caused delays and disruptions for pipeline projects running through Mexico. At least five other pipeline projects in Mexico have been stalled or temporarily suspended due to territorial or environmental disputes. These scenarios also underline hurdles that did not exist before the energy reforms were implemented, which investors will have to face when examining future projects.

Outlook for Mexico’s gas market. What are the likely takeaways from this analysis? The most obvious takeaway is that Mexico will be the largest consumer of natural gas and LNG from the US for some time. Various forecast models show Mexico’s natural gas demand growing to 9.2 Bft3d–9.7 Bft3d by 2030/2031, and increasing by more than 20% from 2015–2016. In its long-term outlook, SENER forecasts domestic natural gas use to peak at 9.87 Bft3d in 2028.

Also, more pipeline growth will be seen for natural gas, as opposed to LNG projects. Mexico appears to be embracing its role as the main consumer of US natural gas, and making pipelines a key priority. As part of its 2018–2022 business plan released earlier this year, Mexico’s CFE wants to ensure that pipeline projects under tender are completed on time. Two greenfield LNG projects are speculative, but one brownfield project is in the early stages and may have a better chance of being developed because of its established location and terminal. A diversified import/export hub may be a more cost-effective option for investors.

The future auction of unconventional gas blocks could offer a sign of future investment for the production of natural gas from shale. Mexico experienced success with its shallow water auction in June 2017 and its deepwater auction in January 2018. If future auctions, especially for unconventionals, go well, it could help unlock Mexico’s significant natural gas potential.

With Mexico’s presidential elections approaching, companies that are serious about doing business in Mexico may have a sense of urgency to establish contracts before President Enrique Peña Nieto’s final day in office on November 30, rather than taking a “wait-and-see” approach. Additional investment incentives will encourage project development and further Mexico’s natural gas transformation. GP

Comments