Why New England pays a premium during peak gas demand

D. Hagan and J. Rueger, White & Case LLP, Washington DC

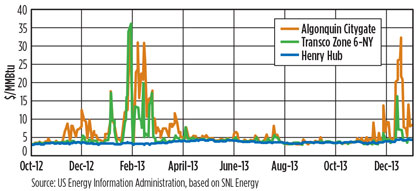

Last winter, New England experienced one of its coldest winters in more than a century. The resulting demand for natural gas sent daily gas prices in New England spiking to $30/MMBtu over the US Henry Hub benchmark gas price (Fig. 1). Transmission organization ISO New England shows that New England’s wholesale energy prices last year were nearly $3 B more than in 2012.

|

|

Fig. 1. Last winter, extremely cold weather increased gas prices in New England |

Near New England’s western border, the Marcellus shale region in nearby New York and Pennsylvania recorded a huge gas surplus. According to the latest figures from the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), Marcellus proven natural gas reserves now comprise the largest shale play in the US. A producer in the Marcellus can often fetch gas prices at a slight discount to Henry Hub prices.

This scenario means that New England gas consumers pay higher prices primarily because there is inadequate gas pipeline infrastructure to allow New England consumers to enjoy the benefits of nearby gas reserves. Tapping the Marcellus shale play to a much greater extent could transform New England’s economy, since lower energy prices could help create more jobs and attract greater business investment. New England already relies on natural gas for half of its power-generation needs, in addition to winter heating, and its need for gas may continue to rise in the coming years (Fig. 2).

|

|

Fig. 2. Workers install a natural gas pipe at a construction site. Image courtesy |

Barriers to new pipeline investment. New England faces a series of barriers that are thwarting and delaying investment in pipelines. First, the region’s deregulated gas and electricity markets do not provide inducements for expanding pipeline capacity. Gas-fired plants have little financial incentive to hold firm pipeline capacity, and pipeline companies are missing a key source of financing from the generators.

Pipeline builders typically need firm capacity commitments of seven to 20 years to secure enough financing to build a pipeline. However, in the deregulated New England electricity markets, firm capacity commitments are only made for one-year periods, three years in advance; and many gas-fired plants are not selected by ISO New England to run often or predictably enough to justify the steep cost of holding firm capacity.

Moreover, if gas-fired plants run short of gas in a high-demand period (such as a cold winter), there is little spare pipeline capacity available for procuring gas from local distribution companies (LDCs).

In addition, multi-state pipeline projects in New England must meet a complex tangle of regulatory requirements (interstate, state-by-state and environmental), which can significantly delay or even cancel a long-distance pipeline project. At the same time, New England is one of the country’s most densely populated areas, with more than one million landowners. Securing easements from many landowners for a greenfield pipeline project is a time-consuming process that adds to regulatory uncertainty.

Several pipeline projects on the drawing board could provide New England with some relief in times of high gas demand, but analysts are divided on whether—and when—these projects will come to pass. For example, Kinder Morgan’s Northeast Energy Direct conduit, set to start in late 2018, would connect New England to the Marcellus shale fields in Pennsylvania. The project has secured approximately 0.5 Bcf of firm commitments. However, it needs another 0.3 Bcf of commitments to make it viable. While analysts expect the project to sign enough customers, the main obstacle is that it would involve a sizeable chunk of newbuild in the nation’s most densely populated region.

Spectra Energy’s Algonquin Incremental Market pipeline, slated for late 2016, is another fully subscribed expansion project to transport gas from the Appalachian Basin of the Marcellus shale play in Pennsylvania. At present, the project is wending its way through the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s (FERC’s) approval process. However, questions remain about whether the project will go forward, and at what cost.

Some efforts have been made to improve investment incentives in the region. For example, New England has made a series of changes to electricity market trading that offer the prospect of improving market efficiency. By the end of 2014, electricity producers in New England will be able to change their fuel supply offers during the operating day to take into account changes in fuel prices.

Starting in 2018, to help ease transmission bottlenecks, a pay-for-performance scheme in the forward-capacity market will be geared at improving resource performance and boosting investment by transferring payments from resources that over-perform in periods of extremely high demand from those that under-perform.

Tweaking the rules of the electricity markets likely will not be enough to stimulate investment in gas pipelines, however. For that, New England must rethink how it can provide the right incentives.

The search for new approaches. Regulators and industry participants in New England have begun brainstorming and sharing ideas on ways to build more gas pipelines by approaching the problem from several angles.

In December 2013, the governors of six New England states (Maine, Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and Vermont) set up a new regional body—the New England States Committee on Electricity (NESCOE)—to cooperate on energy infrastructure and renewable energy. In January 2014, NESCOE floated an idea to expand the electricity transmission infrastructure to deliver up to 3,600 MW of clean energy into the region. However, those plans were shelved in August 2014 when the Massachusetts legislature failed to pass a bill requiring utilities to sign long-term contracts with Canadian hydropower companies.

In April 2014, NESCOE also proposed a concept under which a single entity would enter into long-term contracts for new or expanded interstate pipeline capacity. The costs would be recovered through ISO New England’s tariff from retail electrical customers.

NESCOE aims to raise firm pipeline capacity by 1,000 MMcfd over 2013 levels. A broad range of stakeholders have generally voiced support for this effort to secure incremental gas capacity. Details of the tariff are yet to be fleshed out, but the tariff must be approved by FERC.

Individual states in New England have recently undertaken regulatory measures to boost natural gas supplies and reduce energy prices. For example, the Public Utilities Regulatory Authority of Connecticut approved a framework to expand three natural gas utilities. Also, two other states now have mandates in place to contract for incremental gas capacity.

Other avenues to consider. One possible way that New England stakeholders could spur more pipeline investment is to use the approach that has been successfully tested in the Southeast US by Southern Co., among others. Several customers receive service under a single natural gas transportation contract that funds new pipeline projects. The multi-party transportation contract helps joint dispatch, and it has built-in efficiencies and economies of scale.

Southern Co. and its operating companies function as a single electric utility under this contract. The plan’s creator believes the approach could work for non-affiliated companies as well, and FERC has proposed changes to its regulations that would support this development in the interstate arena.

Another potential approach is to use the Master Limited Partnership (MLP) Parity Act. If approved by the US Congress, the MLP would extend advantages available to pipeline companies to renewable energy firms to boost clean energy supplies, thereby serving as an impetus to bring onstream unconventional oil and gas resources from new production basins, such as the Marcellus shale.

For example, a pipeline company could install solar photovoltaic panels along a newbuild route, use the electricity generated to power the compressors and sell the surplus back to a local utility, thus providing a steady revenue stream to fund new pipeline construction.

The need for a solution. Whatever New England ultimately decides, two things are clear: The solution must be region-wide, and it must be reached as soon as possible. The region must collectively chart a new course to finance much-needed gas pipelines and related energy infrastructure. Otherwise, New England consumers could be facing steep energy bills for many winters to come. GP

|

Daniel “Dan” A. Hagan is head of White & Case LLP’s Energy Markets and Regulatory Practice and a partner in the Energy, Infrastructure, Project and Asset Finance Practice in Washington DC. He has represented numerous corporate energy clients in regulatory proceedings, commercial negotiations, litigation and enforcement proceedings.

|

Jane Rueger is a counsel in the Washington DC office of White & Case LLP. Ms. Rueger specializes in conventional and renewable energy, regulatory and natural gas fields. Ms. Rueger counsels clients with regard to the negotiation and execution of LNG service agreements and advises international entities considering the export of LNG from the US. In addition, she has assisted clients in the development, permitting and regulation of interstate gas pipeline and storage projects under the US Natural Gas Act.

Comments